in praise of oddballs

There’s a certain kind of person who has always fascinated me: the person with deeply eccentric interests who pursues those interests despite the indifference or hostility of others, and in the end makes a great success of it. An example: A. Wainwright. Wainwright was born and raised in Blackburn, Lancashire, but as a young man fell in love with the Lake District, and eventually contrived to move there. For much of the rest of his life he took every possible opportunity to walk the fells of Lakeland; and, as a man whose marriage was deeply unhappy, he had many such opportunities. The local bus service ferried him from trailhead to trailhead, and as he walked he often paused to sketch the terrain and draw his own maps.

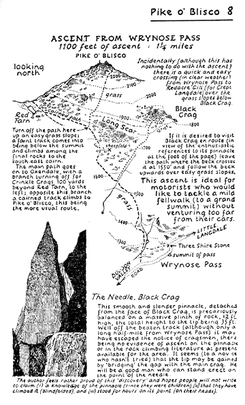

Eventually he decided that he would write his own guides to the fells — but insisted on not just drawing all the maps vistas himself, but also on hand-writing all the text. In the end he produced a large collection of guidebooks filled with pages like this:

These guidebooks proved to be tremendously popular, and are still in print, even though they are outdated in many respects. (They are being revised and updated by a man who once worked with Wainwright.) Wainwright became so famous that other walkers would hail him on the fells, at which point — being grumpy, reclusive, and eccentric — he would turn away and pretend to be relieving himself on the trailside.

I have only been able to hike those fells a few times in my life, but each time I’ve taken the relevant Wainwright book with me. Even when they’re not quite right they’re useful and delightful.

But here’s my point: What in the world ever made Wainwright think that hand-written guidebooks were a good idea? He had to have been producing them primarily for himself, to scratch some deeply personal itch; he couldn't have envisioned an audience of more than a couple of dozen fellow eccentrics. And yet sales of his guides exceeded the million-copy mark when he was still alive.

It makes me wonder what I might have done with my life if I had heeded my inner promptings in the way that Wainwright did — if I had always read just what I wanted to read, and written just what I wanted to write, and did just what I wanted to do whenever I could manage it. I would probably be living under an overpass somewhere: the world rarely rewards its eccentrics in the way that it rewarded Wainwright. But I can't help thinking that we would be better off if more oddballs were as single-minded and indifferent to public opinion as Wainwright was — and if the rest of us were more attentive to what the oddballs are up to.

I’m really into furry porn. Want to come over?

— cw · Jul 12, 04:03 PM · #

I also have a lot of interesting materials re haystacks.

— cw · Jul 12, 04:05 PM · #

Cool! Haystacks was Wainwright’s favorite mountain!

— Alan Jacobs · Jul 12, 04:13 PM · #

Indeed.

— Tony Comstock · Jul 12, 04:34 PM · #

Think about the cost and effort of reproducing that exquisite page layout in the typesetting technology of the day, and suddenly hand lettering is no longer as relatively expensive.

— Matt Frost · Jul 12, 05:00 PM · #

This post immediately reminded me of a similar sentiment on OverthinkingIt.com. Namely #2 on their list of the Top 10 “Best things I learned about America from Independece Day [the movie]”.

http://www.overthinkingit.com/2009/07/01/the-10-best-things-about-america-i-learned-from-independence-day/

It’s actually a pretty good article all the way through. And BTW, if Reihan has never seen this delightfully nerdy pop-culture analysis site, someone please page him.

— John Bejarano · Jul 12, 06:39 PM · #

You’re absolutely right, Matt! — I hadn’t thought of that. I suppose the pressure on him would have been to do simpler and more conventional page layouts, which would have destroyed the effect.

Also, one of the most interesting things about Wainwright’s pages is that hand-lettering offers him infinitely flexible sizing — depending on a range of variables, from desired emphasis to size of accompanying illustration. That could be done via typesetting, but with difficulty and probably with less precision.

— Alan Jacobs · Jul 12, 08:17 PM · #

“Also, one of the most interesting things about Wainwright’s pages is that hand-lettering offers him infinitely flexible sizing — depending on a range of variables, from desired emphasis to size of accompanying illustration. That could be done via typesetting, but with difficulty and probably with less precision.”

Alter the technical specifics and this is more or less why, if you want to make beautiful looking films, it’s cheaper to shoot film than it is to shoot video. There are similar distortions in boat design.

I’m not saying I want to live in the 19th century (fish oil and graphite, yuck!) but there are lots of individual things that actually get worse as a result of most things getting better.

— Tony Comstock · Jul 12, 11:14 PM · #

I meant the grassy type of haystack. Not that into small mountains.

— cw · Jul 13, 01:50 AM · #

I want “Wainwright” in my font menu.

And I always forget that England actually has topography.

— Matt Frost · Jul 13, 03:02 AM · #

Maybe it’s the Lakes. Similar could be said for Beatrix Potter. Here’s a theory: the fells there are just big enough to impress you but just small enough to manage them in a day’s walk. Big tasks seem doable. Maybe being an oddball in the Lakes makes sense.

— Scott · Jul 13, 03:52 PM · #

It’s a whole font family, Matt: italics, title case, everything you need. I’ll get Hoefler & Frere-Jones to work on it ASAP.

— Alan Jacobs · Jul 13, 06:58 PM · #